When he was ten years old his parents sent him to Mulhouse to live with his aunt and uncle to attend a preparatory school. It was there he met a dedicated teacher who inspired him to start studying. From that point on, he had an insatiable* appetite to learn. He decided he would become a minister and follow in the footsteps of his father and grandfather.

He loved music. He started playing the organ as soon as his legs were long enough to reach the pedals, and his family had him studying with a noted organist when he was only five years old. When he was eighteen, he studied with a famous organist named Widor and became an accomplished musician. J.S. Bach was his favorite composer. He would later write a book about Bach.

As he became a man, he began to question why he should be so fortunate to enjoy the life he did when so many other people lived in poverty. This distressed him greatly, and he determined he would do something to make a difference in the lives of those who were less fortunate.

During his 20's he studied and was awarded a degree in philosophy* and also one in theology.* It was during this time he met Helene, the woman who would become his wife. They carried on a secret correspondence for ten years. They shared the same ideals and aspirations.* She would be willing to follow him as he realized his dream of serving others. They were married in 1912 and less than a year later moved to Lambarene in the French Congo (now the country of Gabon) to build a hospital there.

In preparation for this move Schweitzer had gone back to school at age 30 and had become a medical doctor. His wife Helene also had medical training. Their first hospital was in a chicken coop. People would come from the surrounding villages to be treated for all kinds of illnesses.

The next year World War I broke out. Since they were Germans living in French territory, the Schweitzers were considered to be enemies, were detained and put in a prison camp for several years. They returned to Alsace in 1918 and their daughter Rhena was born there. He wrote books about Africa and went to England. There he lectured and gave organ concerts to raise money for the hospital.

He began to build more buildings for the hospital. Eventually there would be 70 buildings housing more than 1,000 people.

His hospital was different from other hospitals because the doctor wanted to accomodate his patients. He knew the people would be reluctant to leave their families to come to the hospital, so Dr. Schweitzer had a series of small huts constructed where people could bring all their family and relatives as well as their animals when they came to be treated at the hospital. They were afraid if they left their families and property at their village they would be robbed while they were away. By letting them bring everything with them, the people were relieved of their worry and healed faster.

They would build fires and cook for their families outside their huts. Dr. Schweitzer would supplement their food by sending someone weekly to the villages to buy bananas and rice. Another doctor or a nurse would accompany the person sent for food and he/she was able to treat the sick people in the villages.

He had an organ especially built for the tropical climate. In the evenings when everyone had retired they could hear the doctor practicing for hours.

Many languages were spoken in the region and few of the patients knew French, so he had orderlies working for him who knew several languages and were able to interpret.

Many older Africans believed Dr. Schweitzer was a supernatural being and wanted to bow down to him when they saw him, but the good doctor dissuaded* them.

While on a journey to see the ailing wife of a missionary, he was able to organize his thoughts and come up with a philosophy which he called Reverence* for Life. He was traveling on a barge being pulled by a small steamer. He started writing sentences trying to bring his thoughts together, and on the third day at sunset as they made their way through a herd of hippopotamuses everything came together for him, and he found the idea for which he had been searching all those years.

Reverence for Life in essence says the one thing we are sure of is that we live and want to go on living as do all living things. He proposed that something was "good" if it maintained and furthered life and brought it to its highest level. He concluded something was "evil" if it hurt or destroyed life or kept it from developing. He urged others to do all they could to alleviate suffering.

He was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1952. When he went to Oslo to receive the prize he was greeted by a crowd of 20,000 people. The Norwegians matched the amount of the prize money; $33,000, and he used the money to build a compound a short distance from the hospital to house leprosy patients. Here people could be housed comfortably and treated for their disease in an environment of acceptance. If they were treated early enough they could sometimes return to their families.

One person who was in that crowd in Oslo was a young doctor named Louise Jilek-Aall. She later went to visit and work at the hospital at Lambarene and wrote an interesting book, Working With Dr. Albert Schweitzer. The following words are from a conversation between the young doctor and her mentor.*

"And if man takes another step and fills Reverence for Life with Love

and the will to protect other living creatures,

then he becomes an ethical human being who,

through his action, elevates life onto a higher plane of existence."

In the 1950's he spoke out against the development of the hydrogen bomb and sparked a world-wide protest against the harnessing of nuclear energy for destructive purposes.

Albert Schweitzer, this great humanitarian,* spent nearly fifty years in the Congo. He died September 4, 1965 at the age of ninety.

This biography by Patsy Stevens, a retired teacher, was written in 2008.

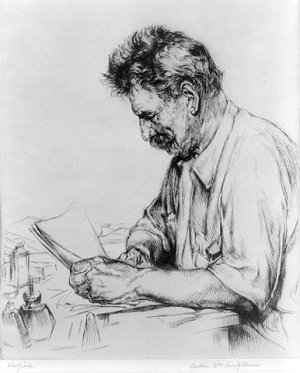

Etching by Arthur William Heintzelman

Etching by Arthur William Heintzelman  A frequent question:

A frequent question: