His clothing was made of flax* which would prick the skin like needles until the shirt had been worn for about six weeks. Once his brother John offered to wear Booker's shirt until it was softer. His first pair of shoes had wooden soles and coarse leather tops.

One of his duties as a boy was carrying sacks of corn to the mill on the back of a horse. If a sack fell off, he might wait for hours for someone to come along and replace it on the horse's back.

One day the slaves were all called to the house of their owner, James Burroughs. A paper was read to them telling them they were now free. His step-father, who earlier had gone to West Virginia, sent a wagon to bring Booker and his family to their new home. The trip took about ten days.

After the move, his mother took a young orphan into the family. Now there were four children; James B., who was the new brother, Booker, John, and Amanda.

His step-father, who worked in the salt mines, got jobs for Booker and John in the salt mines. Sometimes they worked in the coal mines.

Mr. William Davis opened a school for colored children. Booker's parents permitted him to attend if he worked before and after school. He worked from 4:00 AM to 9:00 AM in the mines, then went to school half a day. After school he went back to the mines.

He said his first day at school was the happiest day of his life. When the teacher asked his name he said, "Booker". All the other children gave a first and last name, so Booker chose to take the name "Washington", his step-father's first name, as his second name. He later learned from his mother he did have a second name; Taliaferro.

He soon had to drop out of school to work full time in the coal mine. However, his mother found him another job as a houseboy for the family of General Lewis Ruffner. General Ruffner's wife was very strict with Booker. Once he ran away and started working as a waiter for a steamboat captain, but he didn't know how to be a waiter and failed at the job. He returned to Mrs. Ruffner and she took him back. She arranged for him to get some schooling.

He proved his trustworthiness* to her by selling fruit and vegetables to the miners and carefully accounting for all the money he received. He found being honest always had its reward. He stayed with Mrs. Ruffner four years and came to regard her as one of the best friends he ever had.

He heard about the Hampton Institute in Virginia, a school for black boys and girls. He determined to go to the school. He got as far as Richmond and spent a few days there sleeping under a plank sidewalk at night and loading a ship during the day to earn money to buy food.

He arrived at Hampton Institute and the lady principal told him to sweep a room for her. He knew it was a test. He swept and dusted the room three times until not a speck of dirt remained. He was accepted into the school. He would work as the assistant janitor to pay for his room and board at the school.

His mother Jane died while he was at home for vacation during the summer. It was a very sad time for him.

Miss Nathalie Lord, one of his teachers at Hampton, gave him lessons in elocution* or public speaking. These lessons would prove vital to his success later on.

After graduation he returned to his hometown, Malden, and became a teacher at the first school he ever attended. In the day school he had a class of 80-90 students. He also taught night classes and two Sunday schools. He encouraged several of his students to attend Hampton Institute. He also sent his brother John and adopted brother James to the school.

General Armstrong, the principal at Hampton, invited Booker to return to the school as a teacher and a post-graduate student. He taught a night class for students who had to work during the day. He also taught a class of 75 Indian boys.

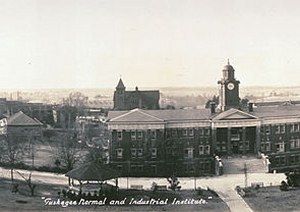

Mr. George Campbell, a prominent white man in Tuskegee, Alabama, wanted to start a school for black children in that town. General Armstrong recommended Booker for the position. The state legislature would give $2000 a year for the school. He started having classes in an old church and a run-down building. When it rained, one of the taller students would hold an umbrella over the teacher's head to keep him dry.

He was able to purchase farmland eventually totaling over 2,000 acres on which to build the school.

He married Fannie Smith and they had a daughter, Portia. Within the year Fannie passed away and did not get to see Portia grow up nor see the school succeed.

All students at the school were required to work in addition to their academic* studies. They chopped trees, cleared land, made bricks, built furniture, and constructed buildings. Classes were started to teach trades and professions

Tuskegee Institute in 1916

Enlarge

Enlarge

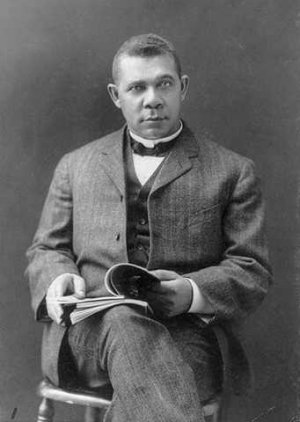

Booker T. Washington was an eloquent speaker and used this skill for the benefit of Tuskegee Institute. The school continued to grow.

Booker married again. Olivia Davidson, assistant principal of the school, was his wife for four years and mother to two sons before she too passed away. Four years later he married Maggie Murray, a teacher at Tuskegee.

Booker T. and his son Davidson picking greens in the garden

In 1895 he was invited to give a speech at an Exposition in Atlanta. In it he urged blacks and whites to work together. Afterward Harvard University gave him an honorary degree.

Friends gave money for Booker and his wife to visit Europe where they had tea with Queen Victoria.

The school flourished. George Washington Carver came to teach agricultural* science. People of wealth took an interest in the education of blacks. Andrew Carnegie helped.

The Washington home in Tuskegee

Booker T. Washington, more than any other black man of his time, helped to elevate his people through education.

This biography by Patsy Stevens, a retired teacher, was written in 2006.

Facts for this story were taken from The Booker T. Washington Papers

Photograph of Booker T. and his son was found in a book "Booker T. Washington, The Master Mind of A Child of Slavery" 1915.

A frequent question:

A frequent question: